Seven Steps To Creating Fictional Magic Systems

Or: You Too Can Make Videogamemancy!

(Before you read the rest of this newsletter, allow me to alert you that I made my first YouTube video! It’s called “3 Reasons The Trench Run is the Best Action Sequence in Star Wars,” and it involves me a) analyzing A New Hope, and b) putting on a cheap X-Wing pilot’s suit. Check it out and give it a thumbs-up if you liked it. I’ll be making more. Slowly.)

My most popular book is Flex, and part of that popularity is that people love Flex’s magic system. And I must have acquired a reputation as “The dude who develops interesting forms of magic,” because whenever a writer friend needs some help designing an interesting system for their novel, they text me.

And as it turns out, I am designing a new magic system for a book I’m planning - so I figured, why not show you how I come up with my concepts in real time?

So let’s go over how to make your book’s magic interesting, through seven simple principles.

Ferrett’s First Rule Of Fictional Magic Systems: Do You Need Consistent Magic?

This is generally another way of asking, “Are your protagonists magicians?”

If your main point of view characters aren’t magic-slingers, guess what? Go nuts! Their magic probably doesn’t matter. Nobody really cares if your villain whips out weird powers during a battle – hell, the “I was saving my best for last” is actually a trope. And if your protagonist has a kindly wizard, welp, Gandalf is the walking epitome of a gumball-dispensing magic – pull the lever, okay, he can do fireworks! Now he can fight a Balrog! Now he’s a horse-riding lighthouse chasing dragons!

Did we know Gandalf could do any of that? Nope. But Gandalf’s not a protagonist so much as he is a plot device to get the protagonists in and out of trouble. So it’s cool.

Brandon Sanderson, who authors are legally obliged to cite whenever they discuss magic systems, says this: The author's ability to resolve conflicts in a satisfying way with magic is directly proportional to how the reader understands said magic.

What that means is that Doctor Strange has been a C-list character in Marvel comics for decades now because he’s cool…. But nobody’s sure when he’s in danger. Doctor Strange comics constantly have him shouting “The Wand of Watoomb! It’s overwhelming my Crimson Bands of Cyttorak!” because, well, we readers have no idea what spells do what.

As such, Doctor Strange stories (and I love Doctor Strange) fall emotionally flat, because he gets beat up until it’s time for him to win, and aside from him bellowing his victory, we have no clue when he’s on the ropes or when he’s triumphant.

Whereas let’s take, say, a cop with a gun. We know what threats she can face, and what threats are gonna pulp her. Her capabilities are known.

There’s a reason cop procedurals get a lot more viewers than your average magician show.

A good magic system exists to tell you when your protagonist’s in trouble. And to do that, your readers have to understand the rules of your magic system well enough that they know what it means when Popeye pulls out his can of spinach.

(That spinach can is a Potion of Strength. Don’t you dare tell me otherwise.)

But magic isn’t just about letting us know the stakes – it’s about -

Ferrett’s Second Rule Of Fictional Magic Systems: What Crazy S**t Do You Want To Happen?

Too often people are like, “I want a magic system!” But magic doesn’t exist in a vacuum.

Magic is your special effects budget.

And when you’re planning a magic system, you need to think about your influences – is this a John Wick-influenced magic firefight, where wizard assassins duck through hallways and blast away scenery with bubinga wood wands? Is this an apocalyptic endgame where your protagonists – Godlike beings struggling to hold onto their humanity – fill the skies with fire? Is this a heist book where your heroes cut their wrists and bleed shadows?

What is the cool stuff you want to happen?

You don’t need much – one or two scenes will do. Flex started with me imagining a girl turning a warehouse pursuit into a game of Metal Gear Solid. But you need to ponder at least a climactic scene, because this magic system is gonna be engineered to making that dream reality.

This is not the time for stunted reveries. Go for broke. Look at all your favorite movies for reference, re-read your favorite books, ponder those childhood shows you adored. This is where you start pinning your favorite movie pictures to your Pinterest board.

Because you’re building your magic system to make that cool stuff happen. You want that Gandalf showdown? That’s your in – now you gotta think of why demons exist, how magic stops them, why wizards can face them down but humans can’t.

This is your time to hammer on your squee-buttons. If you look at Pinterest and shiver with glee, then you’ve found your magic. You should be inspired by this wild image.

BRB, gonna write that story about cutting your wrists to bleed shadows. But that said…

Ferrett’s Third Rule Of Fictional Magic Systems: This Isn’t D&D.

Roleplaying magic is almost invariably about power. How many fireballs can you huck at that ogre before it goes down? Do you have enough Godly sway to heal your broken party?

Which is fine, but that necessity to beat monsters means that RPG magic is all too often about convenience. You don’t wanna think about what the magic costs, you just want it to work. You’re trying to blast that demon back to hell – efficiently, quickly, cutting straight to the triumph.

Literary magic systems aren’t about efficiency.

They’re about raising stakes.

I’m not saying every magic has to have a cost, although that’s a quick way to raise stakes – but the reason Sanderson says Weaknesses are more interesting than powers is because those weaknesses are how you determine what your character struggles with.

A good magic system should define your character’s challenges. With rare exceptions, you want every battle to have stakes – and if those stakes are mushy, or worse, nonexistent, then your scenes suffer. Omniscient wizards are no fun, so you want a magic that:

· Runs predictably out of juice

· Has a cost

· Has a limitation.

You can mix and match – but let’s take that cop as an example. She has a magic wand that we call a Glock 19. That wand:

Has fifteen charges in the chamber before it runs out of bullets.

That’s a predictable number, so if the reader is smart enough to count bullets they’ll know when she’s about to run dry. You can play that for tension.

But it has to be predictable. As noted, because Gandalf isn’t really the protagonist but a walking plot device, he can collapse whenever the plot demands. But knowing when your heroes are about to redline is critical to their key – in Flex, you didn’t have precise measurements when the blowback would overwhelm Paul, but you knew that small changes == okay and big changes == bad. That was enough to rest a trilogy on.

Has a cost associated with firing it.

Our cop hero can’t just fire her Glock willy-nilly into a crowd – she’s got to think of her backstops, of the paperwork she’ll fill out once that pistol is shot, of the fatality of this action.

(If she’s a good person, of course. Let’s say she is. It’s a nice fiction.)

Likewise, your fictional magic might have some restrictions that shape your character’s actions – if you do bleed shadows when you cut your wrists, are you balancing stealth with the fatigue of blood loss? Do you need a magic knife to cut the shadows out? What’s the circumstance under which your heroes can’t pay the cost?

Has a limitation.

The Glock is fatal – you don’t haul it out unless you’re ready to kill. (Unless you’re in that cheap cop drama where they can shoot people in the leg and it somehow doesn’t blow an artery open.) And the Glock isn’t particularly great when some big lug is grappling with you, and it’s not great distance beyond half a block or so. And, of course, you gotta aim it.

All those place tensions. If the perp leaps into a car, they can escape out of range. If the perp steps into a cloud of shadows because they cut their wrist with this weird glowing dagger and a black fog rose up – see, we’re already generating crossover fic! – then our wand-wielding hero’s at a disadvantage.

The last step, that inspiration, showed you what they can do. Now start pondering what they can’t do. It might be psychological – their honor holds them back, they’re afraid of the demon within – it might be physical – in Flex, you can only bend the rules of physics so long before physics strikes back.

But what about this magic will complicate their lives? Why, or when, are they reluctant to use it?

So you’re not only building to that cool-ass moment that’s your inspiration, but you’re thinking why this is a moment of triumph. What has your character broken through to get that awesome scene?

Sidebar: Do You Need A Consistent Magic System?

Everyone bags on Harry Potter because its magic and worldbuilding make no sense when you think about it. The rules are sloppy and contradictory, the world of wizards has bizarre gaps and no consistency.

You know what?

It sold a billion copies.

Look, people come from RPG systems and approach magic like it should all fit together like a puzzle – but the reason Harry Potter is popular is not because its magic is consistent, but because we know how it affects the stakes consistently from scene to scene. The Force isn’t consistent either, but we understand what it means in any given moment.

You can spend a lot of effort locking down your magic so there’s never any contradictions, but very few people care – and a common rookie mistake is to spend so much time designing a complicated, consistent magic system that you need a grad degree in to understand. And they have this magic system that requires so much boring infodumping to comprehend that people bounce off.

(One of the biggest challenges in writing The Flux and Fix, the sequels to Flex, was that the magic system was so complicated that I had to engineer an action sequence at the beginning of each sequel just to rehash how it worked.)

Your magic system doesn’t have to be perfectly correct. It just has to exist consistently enough that when your characters shout “Expelliarmus!” that they go, “Oh, I know what that does.”

If you’re successful enough that people devote YouTube videos to picking your magic system to shreds, congratulations. You’re rich enough that you can afford a little hate.

Ferrett’s Fourth Rule Of Fictional Magic Systems: Can You Make The Magic Personal?

It’s not enough to have strengths and limitations - it’s better the magic stems from who the character is…

…and we’re at 2,000 words for this newsletter, so guess what? Just like Harry Potter and the Deathly Hallows movie, it’s time for an unexpected sequel! Tune back in two weeks when I go over the other four rules. They’ll be shorter, I promise.

But in the meantime, hi, my new podcast is live dissecting the fun IKEA madness of Finna, which was literally nominated for a Nebula award this week, so go and find out why it’s so wonderful.

(And, of course - me, talkin’ about Star Wars.)

With love,

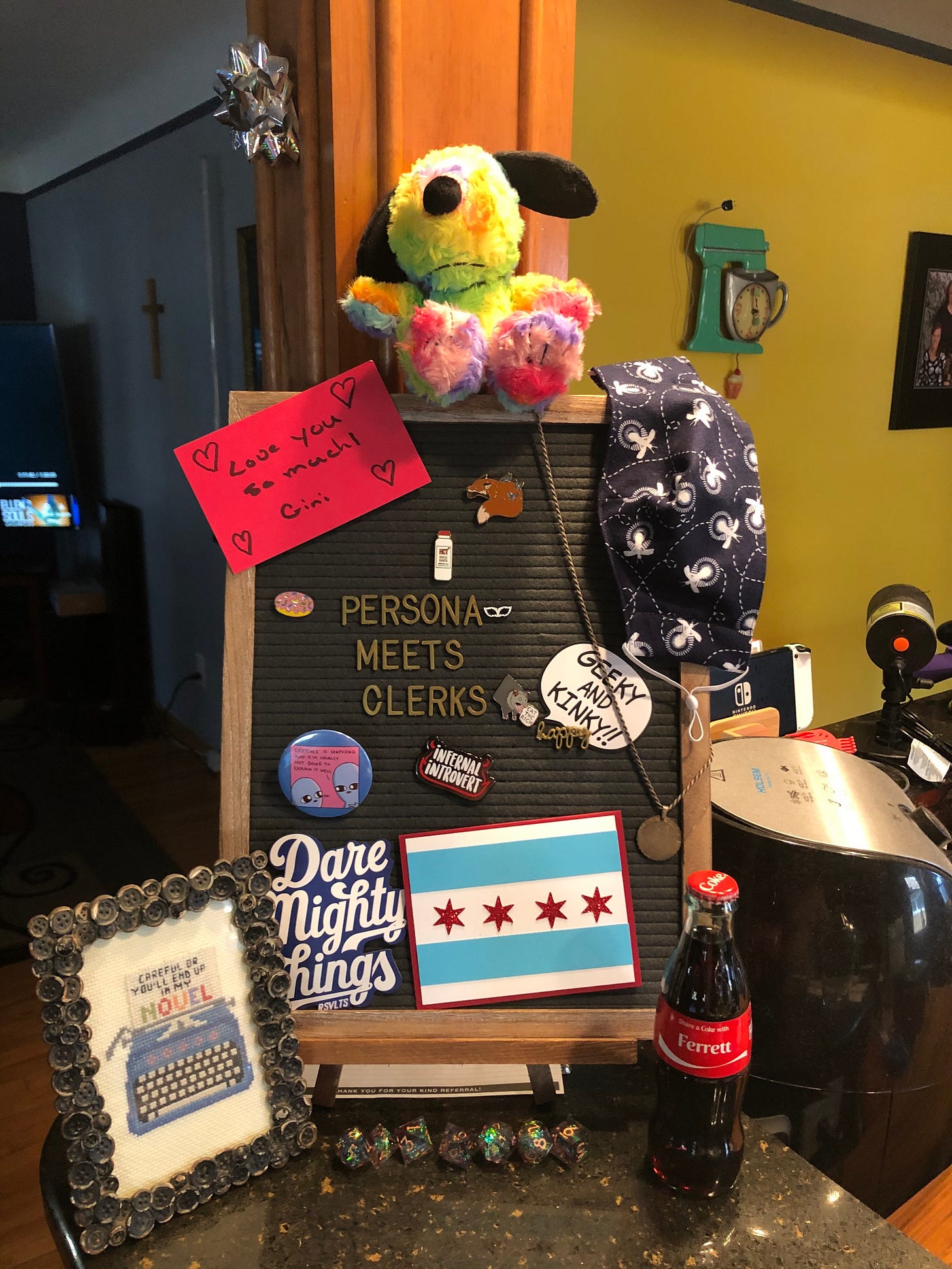

Ferrett

I love this!